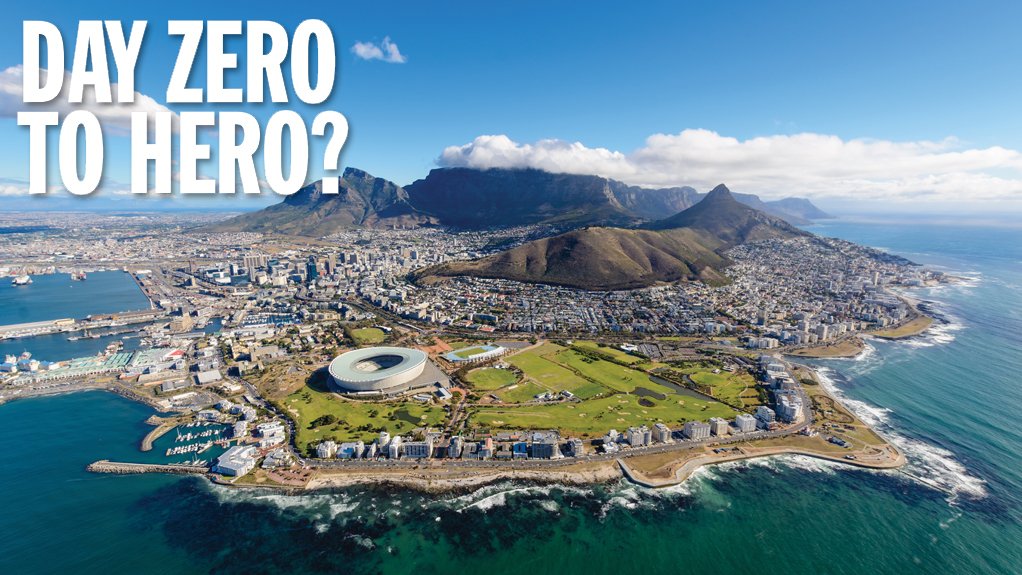

Seven years ago, Cape Town made global headlines for all the wrong reasons.

The city faced the very real possibility that its municipal water supply would run dry amid a severe, multiyear drought, in an event dubbed Day Zero.

A similar, future drought is a distinct possibility, especially amid increasing climate volatility. This time around, however, any weather-related event will be exacerbated by a recent population boom that has seen Cape Town challenging Johannesburg’s position as South Africa’s biggest city.

Triggered by the events of 2017 and 2018, the City of Cape Town (CoCT) has developed what it calls its New Water Programme (NWP) to ensure it does not rely on rain alone to fill its taps.

Within the NWP, there are two significant multibillion-rand projects – one aimed at purifying wastewater to a standard that can be consumed at tap, and the other at desalinating and treating seawater for the same purpose.

Both require meticulous planning and continued management, and expansive community consultations, combined with a mind shift among Capetonians about the water that flows from their taps.

The Faure New Water Scheme

The Faure New Water Scheme will aim to produce up to 100-million litres a day (starting at 70-million litres a day) of purified, recycled drinking water once completed, says CoCT Water and Sanitation MMC Zahid Badroodien.

The project will take wastewater, treated at the recently upgraded Zandvliet wastewater treatment works (WWTW), and clean it further at a water purification plant, located at the Faure water treatment plant (WTP), to produce safe, drinking-quality water that meets national and international quality standards, he notes.

Wastewater treatment plants such as Zandvliet typically collect wastewater from a network of pipes and sewers connected to a city’s homes, businesses, industries and storm drains.

“Globally, purified recycled water is already part of the drinking water system for 30-million people,” says Badroodien. “There are currently 35 cities where water reuse projects are either planned, built or already in operation.

“Cities such as Windhoek, Singapore and parts of the US have successfully implemented potable reuse, demonstrating its viability as a safe and sustainable water source. The city is actively drawing on these experiences to refine its own approach.”

That said, Badroodien notes that the city recognises that public perceptions and concerns around drinking recycled water must be addressed with “transparency, scientific evidence and open dialogue”.

“To build public confidence and acceptance, the city is implementing a comprehensive strategy that prioritises public engagement, education and collaboration.

“Strict protocols will be in place to ensure that Cape Town’s tap water remains safe to drink and that it complies with national requirements.”

Badroodien says the 2017/18 drought was a hard-won lesson for the metro to diversify its water sources, underlining the fact that it cannot solely rely on rainwater.

Tech Behind Faure Scheme

The advanced water purification plant (AWPP) at the Faure WTP relies on a multibarrier purification process to remove contaminants to safe levels, explains Badroodien.

“Nothing about the process is new.”

This AWPP will include the ozonation, biological activated carbon filtration, granular activated carbon filtration, ultrafiltration, UV advanced oxidation and disinfection of the reused water.

In the first step, ozone is introduced into the water to oxidise it and destroy pathogens, viruses and complex organic compounds. This is the first line of defence against potential contaminants, ensuring that harmful microorganisms are neutralised before further filtration.

Biologically activated carbon filtration then removes biodegradable organic substances. It works by fostering the growth of microorganisms that break down organic materials, further purifying the water.

Granular activated carbon filtration absorbs non-biodegradable microorganics, such as pharmaceuticals and pesticides, which sometimes remain in treated wastewater.

Following this, ultrafiltration membranes remove particles, bacteria and viruses that are as small as 0.01 microns.

This is a critical step in ensuring the water is of potable quality by removing any remaining physical contaminants.

The final step is the advanced oxidation process, which uses UV light and chemical oxidation to break down any remaining organic compounds.

Following this, the water should be safe for human consumption.

However, Cape Town says it will take this water and blend it with water from the Theewaterskloof and Steenbras dams – starting at 80% dam water to 20% purified water – and then treat this new mixture again at the Faure WTP, before it is distributed through Cape Town’s drinking water supply network.

“The Faure scheme will use real-time monitoring and control systems to ensure that the water meets local and international safety standards at all times,” adds Badroodien.

“This level of oversight allows for immediate adjustments if any deviations in water quality are detected, maintaining consumer confidence in the safety of reuse water.

“The project will follow a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points, or HACCP, approach, similar to practices in the food and beverage industry, which ensures that every stage of the treatment process is monitored for safety.”

Road Ahead

A final decision on the implementation, operation and maintenance of the Faure New Water Scheme has not been made yet, says Badroodien.

“The city is currently pursuing a Section 78 process of the Municipal Systems Act, No 32 of 2000 (MSA) and a Section 120 process of the Municipal Finance Management Act, No 56 of 2003 (MFMA), where we are busy with a S78 (3) feasibility study to determine the best option for the construction, operation and maintenance of the scheme.”

In other words – the city is still determining if the scheme is viable.

The planning and design process behind the project is, however, complete.

One option to fund the project, with an estimated construction price tag of R3.2-billion, is a public-private partnership (PPP), which is under investigation as part of the feasibility study, along with a city-build-and-operate scheme, and a city-build and private-sector-operated scheme as a hybrid option.

Section 78 of the MSA and Section 120 of the MFMA pertain to a regulated process, adds Badroodien.

“It requires views and recommendations from National Treasury and will also require a city council decision on the preferred option once the feasibility study is complete.”

The estimated starting date for drinking water to potentially flow from the Faure scheme is 2030/31.

Paarden Island Desal Plant

As Day Zero started to approach in the seaside city in 2018, it was hard not to recall Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner: “Water, water every where, Nor any drop to drink.”

The Paarden Island Desalination Plant project proposes building a desalination plant next to the Atlantic Ocean, as had been the suggestion from many sources back then.

Desalination, however, is not cheap.

The Paarden Island project will be a seawater reverse-osmosis plant, where seawater is pumped at high pressure through permeable membranes to produce clean water and brine outflow streams.

The process removes unwanted elements from the seawater and produces demineralised water, which is then treated chemically to comply with the city’s drinking water specifications.

Desalination is used around the world, especially in coastal areas with low rainfall, such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, in the Middle East, Sydney and Perth, in Australia, and Southern California, in the US, notes Badroodien.

The Cape Town project has garnered some resistance, however, as its collection point – the industrial neighbourhood of Paarden Island next to the ocean – is quite close to the city’s harbour, as well as two polluted river outflows, and a marine sewage outfall, where the city pumps sewage into the ocean (as, unfortunately, a number of cities do around the world. And, if not oceans, then rivers).

Badroodien says detailed studies are being undertaken on the feed-water quality.

“This will inform the final design parameters of the desalination plant to ensure the delivery of safe potable water.

“The process design of the desalination plant is robust and international precedent shows that the technology can, with confidence, treat the raw water from the ocean,” he says.

The sources of pollution considered by the project team include river discharge into the ocean from the Salt and Black rivers, as well as the Milnerton lagoon/Diep river system; stormwater flushing during storm events; marine outfalls and harbour contaminants; and other human-related sources.

Badroodien says the treatment processes and design considerations will be detailed in the final feasibility study report, which will be distributed for public comment later this year.

He adds that Paarden Island was selected as the preferred site over Witzands, north of the city, in Atlantis. Both sites are, however, included in the city’s long-term potable water plan.

Site selection criteria included land availability and land-use requirements; existing bulk infrastructure availability; geotechnical conditions; environmental risks; marine and coastal vulnerability; conservation planning; heritage impacts and risks; marine infrastructure constructability; seawater quality; as well as capability of the existing infrastructure to accommodate the addition.

“Compared to Witzands, Paarden Island will be a smaller plant, which enables the city to manage the risk of implementing this novel technology at a large scale, but pave the way for further improvements at larger sites in future,” says Badroodien.

“The location of the plant also enables flexibility in operations and the use of the output water, as it is close to the central business district and main supply pipelines.”

Project Progress to Date

The feasibility study to assess the Paarden Island project’s affordability, value for money, optimal service delivery mechanism, procurement strategy and due diligence is well under way, says Badroodien.

The project’s needs analysis has already been completed, along with the technical solution options analysis, the service delivery options analysis, and the delivery mechanism summary and interim recommendation.

The stages currently in progress are due diligence (ensuring the legal, environmental and site enablement considerations are addressed); value assessment and economic valuation (evaluating the affordability, risk transfer and procurement options); and the procurement plan (developing timelines, governance processes and approval requirements).

Looking ahead, another round of public participation is scheduled for later this year, before the submission of the feasibility study to the city council.

It is anticipated that council will make a decision on the appropriate service delivery mechanism by the end of the year. This decision will then inform the planned implementation timeline.

The construction cost estimate is roughly R5-billion, excluding VAT (as determined at the June 2023 base date).

“The start of construction depends on the outcome of the feasibility study, and the procurement process selected following the council’s decision,” says Badroodien.

Funding options and operating models, including a PPP, are dependent on the feasibility study, and have not yet been determined.

“The current feasibility level information does not indicate the need for land reclamation from the sea,” says Badroodien.

“While desalination is a significant investment, it provides a reliable, climate-resilient water source,” adds Badroodien.

“The feasibility study, conducted in collaboration with National Treasury’s Government Technical Advisory Centre, is exploring the most cost-effective financing and operational model to ensure affordability, value for money and sustainability.

“Treasury’s views and recommendations will be obtained prior to the decision being tabled before council, to ensure it is being considered in the decision-making process.”

Badroodien says various public and private entities in South Africa have small or medium- size reverse-osmosis plants – but not near the scale of the proposed Paarden Island scheme – to desalinate water for bulk supply, such as in Mossel Bay, Knysna, Sedgefield, Plettenberg Bay, Bushman’s River Mouth, Lambert’s Bay, Elands Bay and Richards Bay, among others.

“This is set to increase in the future.”

What Will it Cost?

At a tally of well over R8-billion for these two projects alone, can Capetonians expect to pay significantly more for their tap water as the city rolls out its new water supply programme?

“Generally, the CoCT always seeks to keep tariffs as low as possible,” says Badroodien.

“Currently, residents pay, on average, between 6c a litre and 8.5c a litre for tap water, with this tariff used to recover the cost of supplying a reliable water service.”

He says this includes the costs associated with the establishment of water catchment infrastructure, water treatment, the operation of the distribution system, as well as infrastructure maintenance – including the city’s 11 966 km of water pipes, 12 water treatment plants, 150 reservoirs, more than 9 975 km of sewer pipes, 420 wastewater pump stations, 164 water pump stations and 23 WWTW.

Badroodien does not, however, provide a number for any potential future water tariff increases as the Faure scheme and Paarden Island projects are rolled out.

The New Water Programme

Cape Town’s NWP aims to add 300-million litres a day to the city’s tap water supply by diversifying away from rainwater alone.

Currently, the coastal city uses about 950-million litres of water a day in summer, with usage trending lower in winter.

It is estimated that water use will increase by 2% a year as the population grows.

Badroodien says the residents of Cape Town deserve credit “for saving Cape Town during the drought”.

The combined impact of the 2017/18 measures was a 40% reduction in water use compared with pre-crisis levels, which is equivalent to 32-billion litres.

“That is a remarkable achievement. At the start, many residents were resistant, but, by late 2017, almost every Capetonian was playing their part. This, together with the return of some rain, enabled Cape Town to avoid Day Zero.”

Apart from the Faure Scheme and the Paarden Island project, the NWP includes the clearing of water-guzzling invasive plant species in the city’s key catchment areas, as well as tapping into aquifers.

The city also has a water demand management programme that focuses on reducing demand to ensure supply sustainability.

This includes pressure management, as well as the maintenance and upgrading of water infrastructure to prevent water loss.

Badroodien says the city is aiming for 75% of its tap water to come from surface water by 2040; 11% from desalination; 7% from groundwater; and 7% from reuse.

The installation of grey water systems at household level to save on drinking water is, however, encouraged, but not required.

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY FEEDBACK

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here